That Red Light

We use GIS for a bit of detective work with lines of sight, compass bearings, viewsheds and webmaps.

(I’ll apologise at the outset for the quality of some of the images in this post. My camera doesn’t work that well in low-light situations.)

As we stood out on the porch of friend and colleague Erin’s house in the Beckenham Loop one evening, she looked up on the hill and said, “there’s the red light again. I wonder what it is?”. Sure enough, a bright red light was visible up on Cashmere Hill. Was it a car’s stop light? No, it stayed on and in the same place while we watched. A business perhaps? Curious.

I didn’t think much more about it until another evening when, whilst walking the hound, I saw it from close to where we’re living. “Curiouser and curiouser,” as Alice said. Surely I could use GIS to find that, right? And so the saga began.

One thing I noticed was that the light wasn’t on every night, so I had to wait for it to get flicked on. The same red light is visible from two locations, so there’s something in there about visibility, but also about angles, or more appropriately, bearings. Calling back to my sailing heritage, how about I take bearings on the light from the two locations and then see where those lines cross? Sailors will know that this approach can get you close to a location but not exactly there. (A third bearing would help, but that came later.)

From the street one night I saw the light but didn’t have my compass handy, though I did note that it was just a bit to the right of a line of sight to the transmission tower on the top of Sugarloaf. I could also see the light from near the garage but just to left of the line of sight to the same tower. Here’s what that view looked like during the day with the transmission tower barely visible in the centre distance:

I found it surprisingly difficult to relate what I saw from this perspective on the ground to where it might be on the Google Maps or Earth, so more work was needed.

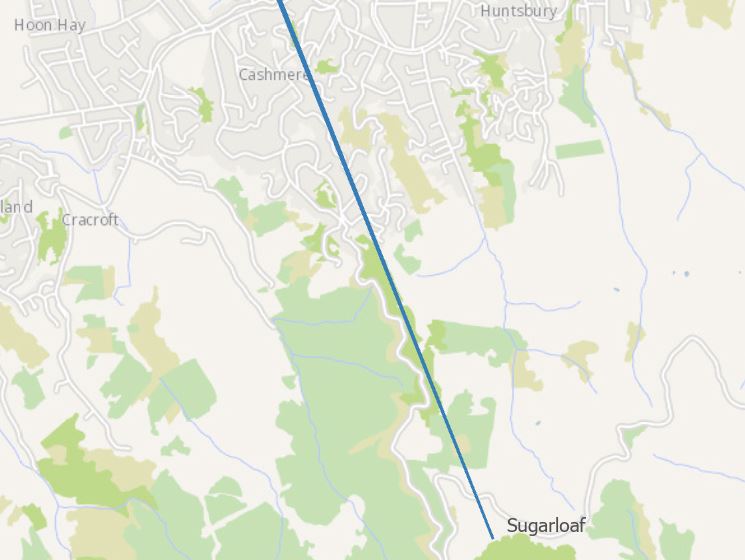

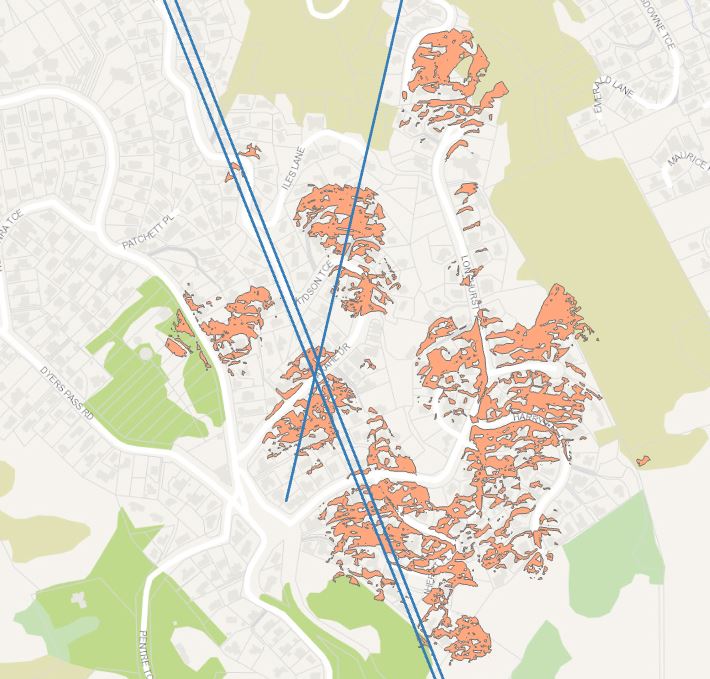

Having the two lines of sight meant that I could draw both lines on the map and know that the light was somewhere between those lines (not showing the origins to protect my privacy!):

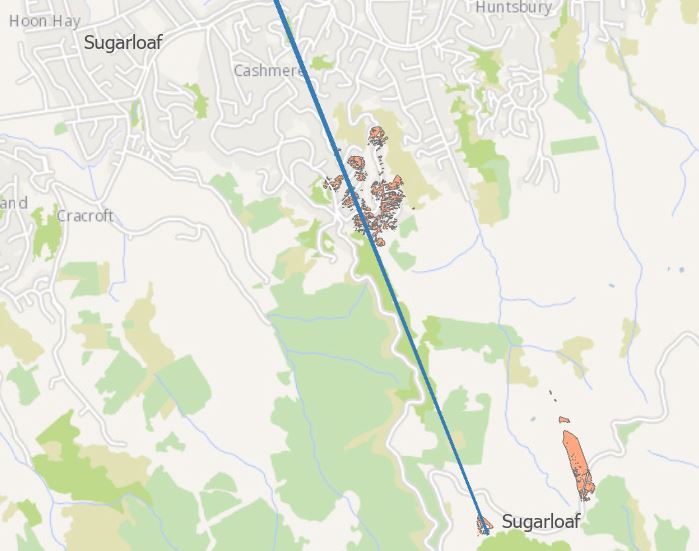

Since I knew that the light was visible from both our locations, I next created viewsheds from the garage point and from Erin’s porch (using the 1m DEM) and then intersected them – this would show me the areas that were visible from both places:

(The intersected viewshed is in orange.) Zooming in a bit more on the most likely areas, we’re narrowing things down:

The most likely place for the red light is between the blue lines and within the orange viewshed.

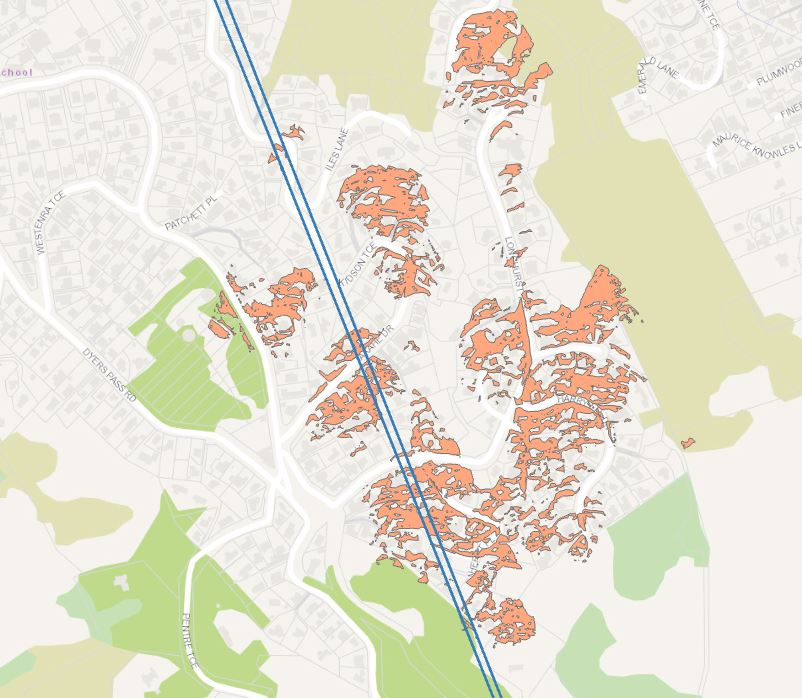

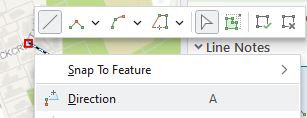

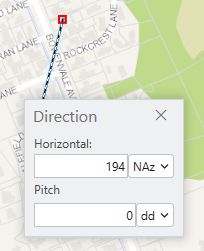

I could really use another bearing to narrow this down even more, so I asked for Erin’s help: she bravely took a magnetic compass bearing of 170⁰ magnetic to the light from her porch. Correcting for compass variation (aka magnetic declination, ~24⁰ these days) made it 194⁰ true, I could then draw that line on the same map. A nice thing I could do here is click on her porch location on the map and then set the true bearing by right-clicking > Direction

and using the corrected bearing (for a random point – not Erin’s house!):

Extending that line beyond my lines-of-sight and looking in the bi-visible areas (Ed. Eh? “Bi-visible”? Talk about poetic license.) would tell me roughly where the light was, right?

Armed with this knowledge and trying not to be too creepy, I headed up the hill one night when the light was blazing brightly.

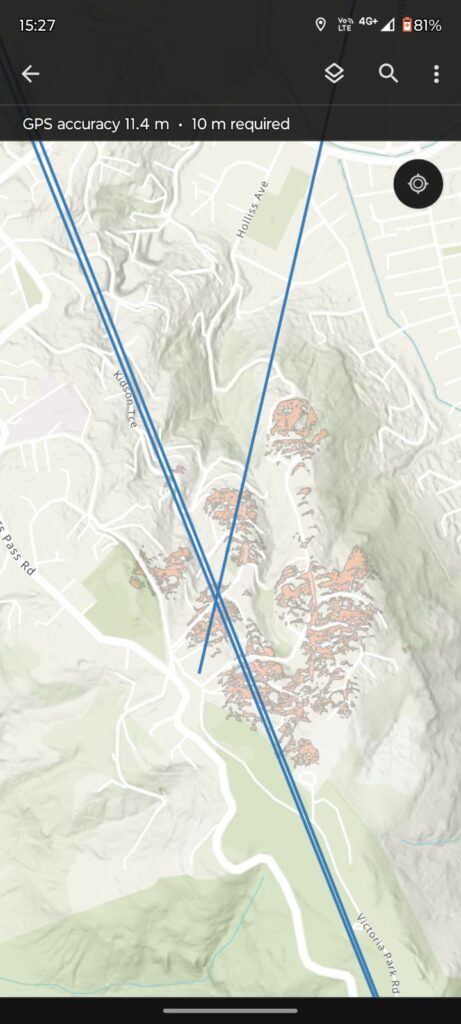

To try and make things a little easier, I set up a webmap and used the Field Maps app on the phone to know how close I was to the lines and viewsheds:

And found it!

To protect everyone’s privacy, I won’t show you exactly where it was, but it wasn’t too hard to find it once I got close enough and it was within the joint viewshed. The upshot is that the light is at somebody’s house and seems to just be a kind of mood light, or maybe a neon sign as best I could tell. It just happens to be very visible.

Incidentally, courtesy of this, I discovered a neat little addition to visibility analysis in Pro. Within a 3D scene, and with the right basemap set, one can set up a dynamic, real-time viewshed. It’s not easy to capture this in static images, so below is a quick video that shows how it can be done – you can only do this in a 3D scene:

“Alright Mr DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up”

This isn’t the first time we’ve used GIS for a bit of detective work and I hope I can be forgiven for being perhaps too obsessed with GIS, but it was a fun exercise of combining navigation skills, viewsheds and mapping to figure something out, which, in a nutshell, is sort of what GIS is all about, right?

C